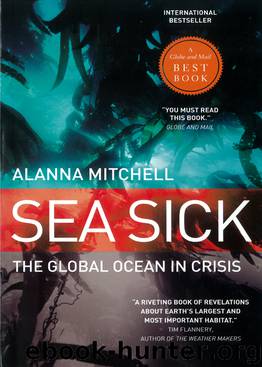

Sea Sick by Alanna Mitchell

Author:Alanna Mitchell [Mitchell, Alanna]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 978-1-55199-341-6

Publisher: McClelland & Stewart

Published: 2010-03-01T16:00:00+00:00

On day five only four corals spawn. No eggs are fertilised. Everyone is exhausted.

Day six and from the second Knowlton gets into the water, she knows that tonight is the night. The water is electric. Even land creatures like us can feel the sexual charge. It’s as though the whole reef is vibrating.

It’s 7:40 p.m. The first group of divers is already underwater, scouring the reef with high-powered flashlights, prepped with red glow sticks to mark anything interesting. At 7:43 Knowlton spots the first colony of corals getting ready to spawn.

Then, right on cue, it starts. The first bundle of eggs and sperm that the scientists are tracking heads up at 8:05, then another at 8:06, 8:08, two at 8:11, another at 8:12, 8:13, 8:14, 8:18 and then a couple of laggards at 8:21.

Divers follow them up, releasing red glow sticks to follow the bundles. That way, the two members of the team who are in a rowboat can follow the eggs and capture some of them in plankton nets. Later in the lab we’ll look at them under the microscope to see what percentage is fertilised. It will give us a clue to how successful this year’s spawn is.

I’m hanging on the surface again with my mask and snorkel. The air fills with a pungent salt funk. The whole reef is having sex. I can’t see the bundles pop out but I can see them rise, pink and delicate, in the arc of my flashlight. And I can see the tiny creatures who are gorging on all this great egg and sperm protein. It’s a feeding frenzy as much as a sexual one.

This is what all the reef organisms have been waiting for all year. It is a moment of exquisite hope.

Suddenly, though, there’s lethargy. As if the reef is having a leisurely smoke at the end of it all.

The divers surface to change spent air tanks and plunge again. By 9:20 the other two coral species are ‘setting’. At 9:46 the second spawn has begun and the surface fills again with ectoplasm, the salt smell of sex and the eerie red light of the scientists’ chemical glow sticks.

Finally, the spawn is done. Triumphantly we take our night’s work to the lab, calling ourselves Team Spawn. We’ve gathered coral eggs. Now we have to wait to see whether they’re fertilised and will start dividing into coral embryos. And, if so, what percentage.

By 4:15 a.m. hope is beginning to fade. Some years, every single egg sampled has been fertilised; tonight it’s about half. Plus, team members—waterlogged and bleary-eyed—have added up the numbers and found that only about half the coral colonies that could have spawned did.

Biologically, these are not great odds. This ancient, magnificent rite of nature, so painstakingly catalogued tonight, has probably failed to produce enough baby corals.

On the other hand, in the whole long history of coral spawnings going back perhaps 450 million years, humans have witnessed and tried to catalogue just a few. Maybe in the grand

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(4748)

The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us About Coming Conflicts and the Battle Against Fate by Kaplan Robert D(3602)

Zero Waste Home by Bea Johnson(3297)

COSMOS by Carl Sagan(2959)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(2953)

Good by S. Walden(2920)

The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire (The Princeton History of the Ancient World) by Kyle Harper(2442)

Camino Island by John Grisham(2391)

A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley(2367)

Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation by Tradd Cotter(2314)

Human Dynamics Research in Smart and Connected Communities by Shih-Lung Shaw & Daniel Sui(2181)

The Ogre by Doug Scott(2119)

Energy Myths and Realities by Vaclav Smil(2066)

The Traveler's Gift by Andy Andrews(2017)

Inside the Middle East by Avi Melamed(1946)

Birds of New Guinea by Pratt Thane K.; Beehler Bruce M.; Anderton John C(1915)

Ultimate Navigation Manual by Lyle Brotherton(1770)

A History of Warfare by John Keegan(1722)

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts(1620)